The first, or at least the most lasting thing I remember about the actor David Garrick was his hydraulic wig. He wore it while he was playing Hamlet; on Hamlet’s first encounter with his father’s Ghost the hair on the back of Garrick’s head literally stood on end.[1]

Exactly how it worked I don’t know: presumably Garrick had a button somewhere he could press that made the back of the wig slowly rise up from his head at the appropriate moment. How long it remained there is not on record.

You’d think – I certainly did – that meant he was a pantomime actor, fond of tricks and melodramatic jiggery-pokery, but actually you’d be totally wrong.

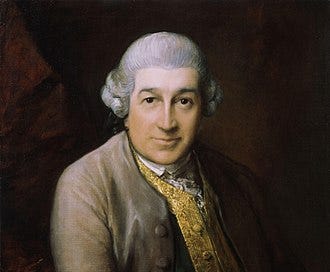

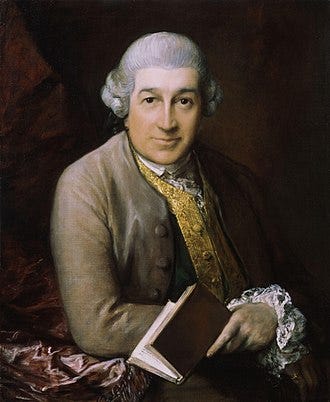

Of the famous actors down the centuries there is one – or sometimes two – in every period whose legacy becomes legend. Richard Burbage (and arguably Ned Alleyn) in Elizabeth England, Thomas Betterton and Mrs Elizabeth Barry in the Restoration, David Garrick in the eighteenth century followed by Edmund Kean, the Kemble family and Mrs Siddons, William Macready, Henry Irving, Ellen Terry, Lawrence Olivier and so on. Most of them have streets or theatres named after them. Many have had plays written about them.

What makes them so special? Is it their acting talent, or their skills at promotion, self- or otherwise? Did they break new ground?

Perhaps there’s a bit of all of those. Burbage had the distinction of being the first to play many of Shakespeare’s heroes, from Hamlet to Lear to Richard III, and even to have roles written for him by the most famous playwright of all time. Alleyn became hugely wealthy – through his business ventures rather than his acting – and founded a school. Betterton shines as a beacon of uprightness and sobriety in an age when very few people appeared to be either. Mrs Elizabeth Barry became known as the best tragedienne ever seen on stage after a sticky start.

Garrick was credited – along with others including Charles Macklin, who coached him – with introducing a new and revolutionary naturalistic style of acting, which prompted the comment from an older actor of the ‘declamatory’ style called James Quin:

“If this young fellow is right, then we have all been wrong.”[2]

This suggests Garrick was not adapting the prevailing acting style so much as creating something that had never been seen before. Of course by comparison with the histrionics of the Restoration ‘naturalistic’ is a relative term.

According to his own description as an actor Garrick was above all a man of technique. He boasted once that he could emote as effectively to a post as he could to a flesh and blood woman playing Juliet. He had a party piece where he ran through the whole range of emotions without showing any himself. It’s said he ‘stood outside his characters’ and never became fully engaged with them, which won the approval of French philosophe Denis Diderot, who believed an actor should be devoid of personal emotion.[3] He encouraged his fellow players to follow his lead and ‘borrow from nature’, and to bring the audience to them rather than allow themselves to pander to the audience.

Whatever technique he used, it worked.

Like many of that era Garrick was not just an actor but a playwright and theatre manager as well. He made his name overnight as a young Richard III at the Goodman’s Fields Theatre in Whitechapel, which somehow skirted the strict licensing on straight theatre by sandwiching Shakespeare between musical interludes. The following year he was taken on at the Drury Lane Theatre and three years later, at the age of thirty, he took over the management of Drury Lane and ran it until his retirement in 1776.

On the opening night of his tenure at Drury Lane he delivered – or rather an understudy delivered it for him as he was indisposed – a speech everyone assumed was written by him, in which he claimed the Restoration stage had been dominated by “immorality and obscenity” and “shamelessly catered for the pleasure-seeking audience.” The future of theatre, he said, lay in the hands of the audience, and he and his fellow players were helpless in the hands of rapidly changing tastes.

The speech was actually not written by Garrick but by a “struggling literary hack” by the name of Samuel Johnson, who for some reason was not credited.[4]

During his time at Drury Lane Garrick produced most of Shakespeare’s plays, some but not all in their original form. He gave Macbeth a death speech and he retained the Nathum Tate version of King Lear complete with the happy ending, albeit with some of Shakespeare’s text restored.[5] It’s said he paid his actors well and even introduced sick pay.

In 1769 Garrick was made burgher of Stratford upon Avon, Shakespeare’s birthplace, and he helped put the small market town firmly on the map for the first time by organising an extravagant Shakespeare Jubilee, which took place over three days and was almost washed out by continuous rain and an overflowing River Avon.

He also apparently introduced new scenic and stage designs, which included the gradual retreat of the apron stage so the action took place within or upstage of the proscenium arch. He was instrumental in taming audiences, removing them from the stage itself and encouraging them to sit quietly and pay attention to what was happening on stage rather than chatter and squabble among themselves. He got rid of those libertines who thought they could wander backstage in and out of the ladies’ dressing rooms at will.

Along with this new respectability the theatre auditorium became gradually more hierarchical. The poshest seats were in the boxes, followed by the pit, the gallery (what we would now call the dress circle) and the upper gallery. The new well-behaved audiences were mostly from the moneyed classes and while many of them were there to be seen rather than to see, they by and large kept quiet. So the scene was set, audience-wise, for the next two hundred years or so.

Next: Garrick’s women

Sources:

Representing Shakespearean Tragedy, Reiko Oya

Shakespeare’s Folly, Johanne M Stochholm

Actors on Acting, eds Toby Cole & Helen Krich Chinoy

[1] https://www.jstor.org/stable/3206806?origin=crossref

[2] Cited in Actors on Actors

[3] Actors on Acting

[4] Representing Shakespearean Tragedy, Reiko Oya, Cambridge University Press, 2007

[5] Representing Shakespearean Tragedy