The theatre patents

Thomas Killigrew and William Davenant

By way of a brief break from the chapter-posting, I’ve been looking into the background to the two theatre patents issued by King Chrles II in 1662. The following will end up in the Appendix.

Until I started looking into things properly I had assumed King Charles II’s two patents had been issued to two companies led by Thomas Killigrew and William Davenant, who had built and run, respectively, Drury Lane Theatre and Covent Garden.

The truth is a little more complicated however.

In a nutshell: only one of the patents, granted to William Davenant, remained operative all through the patent period up until the rules were changed in 1843. The Killigrew patent remained dormant from 1682 right up until 1813. So while Covent Garden was run on the Davenant patent Drury Lane actually relied for a large part of its early life on a series of fixed-term licenses, usually lasting 21 years each.

The full story, if you have the stomach for it, is here: The Killigrew and Davenant Patents | British History Online (british-history.ac.uk). Otherwise below is my version of it, distilled down to the kind of details that a brain like mine can properly comprehend. It’s necessary to explain that while the patents were bought and sold constantly and for the most part were owned by several people at once, many of them ‘sleeping partners’, I have tried to simplify things by concentrating on the people who made things happen, even if they owned only a small portion of the patent in question.

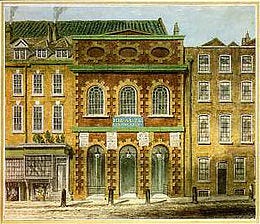

Up until 1682 the two companies operated under their separate patents, initially in Lincoln’s Inn Fields and then at Thomas Killigrew’s theatre in Drury Lane and William Davenant’s at Dorset Gardens. So far so straightforward.

By 1682 however the King’s Company was floundering and so it was decided to amalgamate the two companies under the heading of the United Company, operating under Davenant’s patent but, confusingly, performing largely at Killigrew’s theatre in Drury Lane. Thus the Davenant patent became associated with Drury Lane and the Killigrew patent became dormant.

That was just the beginning.

The Davenant patent found its way into the hands first of the eldest Davenant son Charles and then of his brother Alexander. Alexander mismanaged things and was forced to sell his minority share to a lawyer named Christopher Rich while he fled the country to avoid bankruptcy.

It was while Rich was in charge of Drury Lane that Thomas Betterton and some of his fellow actors, protesting at their treatment by him, debunked and returned to their old home in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, for which they were able to obtain a license[1] from the Lord Chamberlain.

So: in 1695 the Davenant patent was (largely) in the hands of Christopher Rich, the Killigrew patent was still dormant and owned by Killigrew’s son Charles, and Betterton and Co were in possession of a license, not a patent, to perform in Lincoln’s Inn and then at the King’s Theatre in Haymarket, where they stayed until they were forced to return to Drury Lane in 1707.

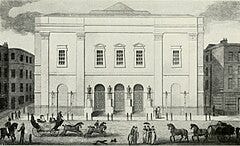

Christopher Rich meanwhile had fallen foul of the Lord Chamberlain and was forced out of the theatre in Drury Lane. He left taking the Davenant patent with him and leased a theatre in Lincoln’s Inn Fields. He died in 1714 before the new theatre was ready and his son John Rich took over both the theatre and the patent; then when he built his new theatre in Covent Garden it was under the Davenant patent.

So by 1732 the Davenant patent was established at Covent Garden, where it remained until the Theatres Act of 1843 rendered the patents redundant.

The following year John Rich and his trustee bought the Killigrew patent, probably for a song, and by 1741 Rich himself was in sole possession of both the Killigrew patent and the Davenant patent.

Here arises the first question: why would one man want to own both patents? There is no indication Rich made any attempt to use the Killigrew patent at any time. My assumption is that it was regarded simply as an investment, like a stock or share, to be sold on hopefully at a profit at some future date.

Meanwhile: how was the theatre at Drury Lane able to operate without a patent?

The answer is by a series of 21-year licenses granted by the Lord Chamberlain – a far from ideal set of affairs, as it was to turn out.

This itself raises a further question as to why the Lord Chamberlain allowed such a strange situation to exist: for most of its life only one of the two patents granted by the King was operational. Why the authorities were not able to insist the Killigrew patent be somehow returned to the theatre at Drury Lane rather than lie dormant for 120 odd years is odd, to say the least. But that was how things were.

John Rich died in 1761 and his assets were bequeathed to his widow and four daughters. In 1767 they sold the lot: both patents and the lease and contents of Covent Garden Theatre. The buyers were four men, two of whom had no connection with the theatre at all.

Eventually one of the buyers, Thomas Harris, bought out the majority of the others. And his plan, along with Richard Brinsley Sheridan – who by now was in charge of Drury Lane – was to build a whole new theatre which they would manage jointly under the authority of the Killigrew patent. For this purpose Harris acquired a piece of land near Hyde Park Corner in 1784, but for various reasons the theatre was never built.

In 1791 Sheridan drew up an ‘Outline for a General Opera Arrangement’ with the proviso that the King’s Theatre in Haymarket – Vanburgh’s opera house – should have a monopoly on opera, the planned theatre in Hyde Park Corner should be abandoned and the dormant Killigrew patent, largely owned by Thomas Harris, should be “annexed inseparably” to the Drury Lane Theatre. (Still with me?)

By 1791 Sheridan was in the process of rebuilding the Drury Lane Theatre and needed more security than a 21-year lease in order to be able to raise the money. How he achieved this without the patent is not clear, as Drury Lane continued to operate under its 21-year lease, which after the fire in 1809 was extended to 1837.

Then in 1810 by an Act of Parliament a Theatre Royal Drury Lane Company of Proprietors was formed and given permission to raise £300,000 to rebuild the theatre and to buy the outstanding shares in the Killigrew patent; but it was not until 1813 that the Killigrew patent in its entirety was finally bought by Drury Lane, where it has remained since.

That’s about it, because as we know the Theatres Act of 1843 put paid to the authority of the two patents anyway. Drury Lane and Covent Garden still held the patents – and still do – though they weren’t worth much since the Act.

There is plenty more, if you care to refer to the link above, which is very comprehensive.

[1] The difference between a patent and a license: the patent was granted in perpetuity, the license had conditions and a time-limit, in the case of Drury Lane usually 21 years.