Joan Littlewood went to RADA? How come such a maverick got to begin her theatre career at such a temple of the theatrical establishment?

The answer is: by her own volition. Unknown to anyone else she auditioned and applied successfully for a grant from the London County Council. In her defence, she claimed she got very little out of the course except for the movement classes, which were based on Laban. As a working class kid she felt so out of place that she ate her lunchtime sandwiches in the lavatory.

Littlewood been introduced to the theatre by the nuns at her school. She had put together a school production of Macbeth, with herself playing the lead plus the Third Murderer and an Old Man, declaiming, “I was producer and my word was law.” The production went down well and she was asked to repeat it but without the gore, which had caused the Mother Superior to faint. She also organised a protest march on behalf of a dead rat.1

Joan Littlewood started, you could say, as she meant to go on.

While at drama school she tied first place with the actress Rachel Kempson in a verse-speaking competition and one of the judges, a radio producer based in Manchester called Archie Harding gave her a job reciting Shakespeare on the World Service at 3am and told her if ever she was in Manchester to look him up; which, eventually, she did.

Manchester

By the time Theatre Workshop came into existence in 1945, after the war, Littlewood had been involved in ‘agit-prop’ theatre in Manchester for ten years or more alongside her colleague Jimmie Miller.2

Miller, a self-taught and self-styled writer, director and activist whom Littlewood had married in 1935 when she was 21, had introduced her first to an association called Theatre in Action followed by Theatre Union. These ad hoc troupes were made up of amateur actors with no theatre experience, and as Miller himself admitted, ‘I don’t believe any of us regarded ourselves as artists or, indeed, as being in any way involved with art. We saw ourselves as guerrillas using the theatre as a weapon against the capitalist system.’3 He and his fellow non-artists regarded the professional theatre with total disdain. They toured their shows – some of them created from improvisation, some based on adaptations of European and American plays – on the streets and in various venues around the north of England. Their production of Last Edition, a part documentary, part revue ‘living newspaper’ caused them to be arrested and fined for ‘behaviour likely to lead to a breach of the peace’.4 Their communist-sympathising activities had already drawn the attention of MI5, and as a result the BBC – on which they had relied for part-time paid employment – were banned from employing them.

Theatre Workshop was set up as ‘both a production unit and a training ground’, led by Littlewood and combining the techniques of Stanislavski and Commedia dell’arte with movement, puppetry, music and voice and with a repertoire created largely by Jimmie Miller, who by then had changed his name to Ewan MacColl.5 They were joined by a woman who had worked with Rudolph Laban called Jean Newlove, who following Joan and Ewan’s divorce in 1948 married MacColl yet continued to work on movement for Theatre Workshop even after MacColl left it.

Then in 1953 Littlewood decided to take a lease on a theatre in east London. By this time Jimmie/Ewan’s role in Joan’s professional and personal life had been taken over by a burly young actor called Gerry Raffles, and MacColl quit the theatre altogether to join a group called the Hootenannys and forge a long and successful career as a writer and performer of folk music.6

The Theatre Royal Stratford East

The theatre was pretty well derelict when they took it over. For those unfamiliar with this grand little building, Stratford East is as the name suggests in the east of London, now a shining city of glass and concrete and a terrifyingly complicated one-way traffic system, in the midst of which still sits this little Victorian theatre, an oasis in a Brave New World of commerce and retail utopia.

Despite their efforts Littlewood & Co could not get the local council to help them financially so they restored the theatre themselves, sleeping overnight in the dressing rooms. They opened in February 1953 with a production of Twelfth Night featuring Harry H Corbett as Sir Andrew Aguecheek. The rest of the company included George Cooper, Avis Bunnage, Rosalie Williams and Howard Goorney and later, Brian Murphy, Henry Livings, James Booth, Yootha Joyce, Barbara Windsor, Phil Davies and Nigel Hawthorne. They presented their plays, including Shakespeare, Brecht and Ibsen, in two-week runs, held classes in local schools as well as children’s theatre on Saturday mornings and music concerts on Sunday evenings.

Yet still the Arts Council refused to help with finance and they were constantly threatened with bankruptcy. The tide began to turn with Brendan Behan’s The Quare Fellow, based on the writer’s own experience of prison life and starring a newcomer called Richard Harris. It transferred to the Comedy Theatre after Littlewood had licked it into shape.

A Taste of Honey arrived on Littlewood’s desk accompanied by a handwritten letter from the nineteen-year-old author Shelagh Delaney explaining she’d written it in ten days as a result of her first ever visit to the theatre two weeks previously. That play packed the house in Stratford East before transferring to Wyndham’s Theatre in the West End, followed by Broadway, a film, and a TV series.

Brendan Behan’s next play The Hostage again won raves reviews across the board and again transferred to the West End and Broadway. Fings Ain’t Wot They Used T’Be was a cockney musical featuring low-life in the East End, written by Frank Norman with songs by Lionel Bart. It transferred to the Garrick and was turned into a highly successful album.

Oh What a Lovely War

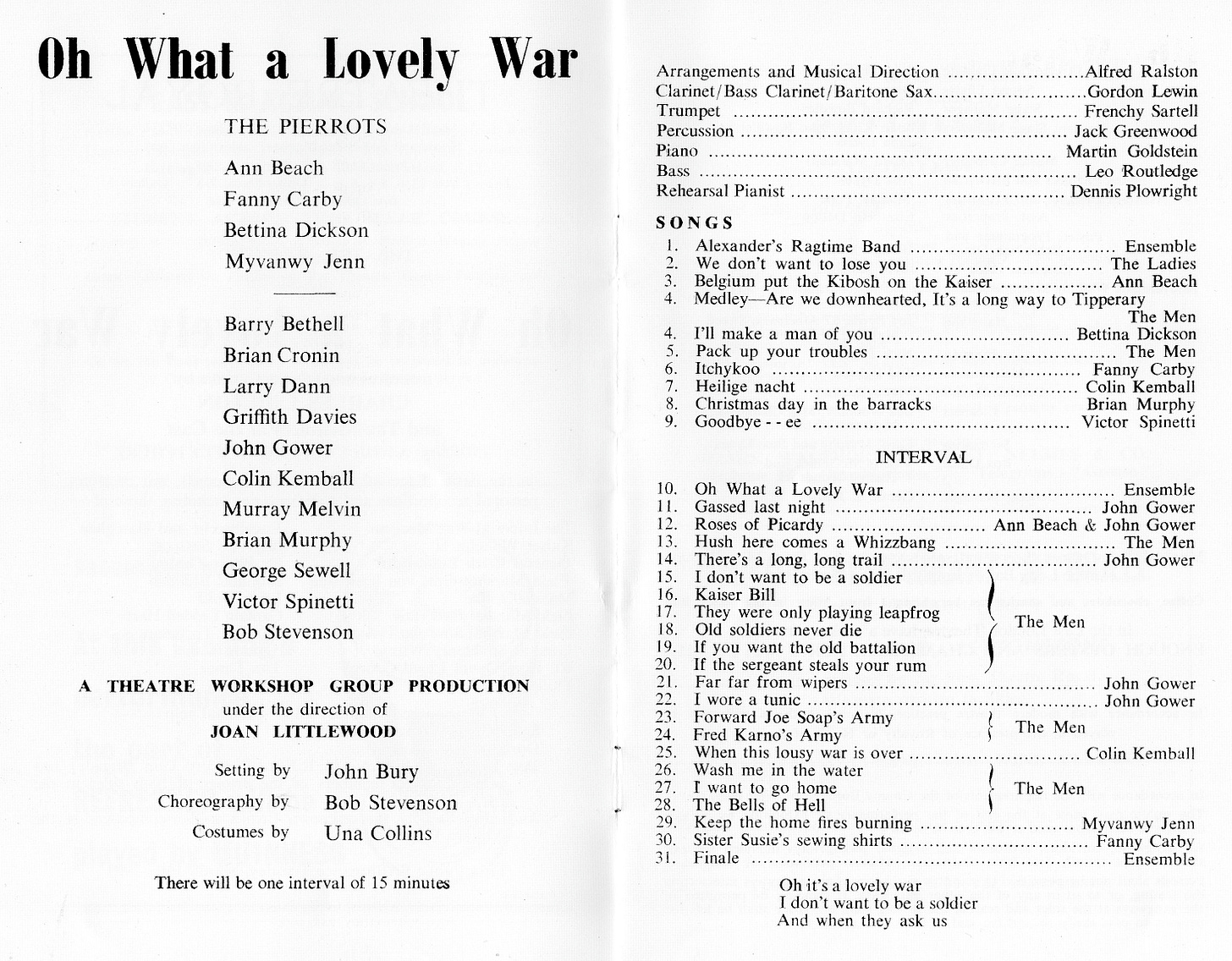

The original production in March 1963 announced itself as ‘a musical entertainment written by Charles Chilton and The Members of the Cast’. It was without question Littlewood’s greatest success.

Gerry Raffles had heard a broadcast on the radio of a musical put together by Chilton called The Long Long Trail, inspired by a visit to the death-place (there was no grave) of his father, who’d been killed in the battle of Arras in World War I. Raffles invited Chilton in to talk to Littlewood about turning it into a stage musical. After some resistance and to avoid her two bugbears of sentimentality and military uniform, and remembering a time when as a child she had become transfixed by a pierrot show on a beach in Ramsgate, Littlewood decided to set the whole thing as a pierrot show with actors in pierrot costumes and using songs of the time. The end result was put together by the cast – which included Ann Beach, Murray Melvin, Brian Murphy, George Sewell and Victor Spinetti – under her supervision and with stage design by John Bury. It transferred to Wyndham’s Theatre in June and thence to Broadway, where it won all sorts of awards before it was turned into a film. And the rest, as they say, is history.7

When Gerry Raffles died of diabetes in 1975 Joan Littlewood quit the Theatre Royal, and the profession, and ended up living in France. She died in 2002 aged 87.

Littlewood’s legacy

Director, entrepreneur, actress, teacher, dramaturg, playwright, self-styled social worker and force of nature. (Have I missed anything out?) A powerhouse, terrifying, eccentric, funny, yet capable of great warmth. This is the impression I have of Joan Littlewood.

Some of her methods were bizarre, to say the least. She had Richard Harris stripping to the buff during rehearsals at one point while telling him to carry on as if he were fully clothed. He claimed to have learned more from her in half an hour than in two years at drama school. Her mantra was not so much ‘the right to fail’ as the necessity of failure. ‘Go on stage to fail,’ she told her actors. ‘If you go out to fail you might be creative.’8 If ever she felt actors were becoming too comfortable she’d throw the spanner in the works by setting them against one another or telling them to change their outfit or their entrance or, on one occasion, swapping roles. She encouraged experiment and was happy to listen to actors’ opinions yet had little time for anyone who disagreed with her. ‘In the end, after all the playing about, it was Joan who told the actor what to do in quite specific terms,’ said one (unnamed) actor.9

She was loved and feared fairly equally. Actors who got on with her were fiercely loyal. The struggle to get funding from the Arts Council continued throughout her tenure at Stratford to the point where she would announce in the programme, ‘This play owes nothing whatever to the Arts Council.’10 In this respect, as in others, there was an obvious rivalry between Stratford East and its better-funded competitor in Sloane Square, whom Joan dismissed as ridiculously middle-class.

Both groups were prone to their own form of snobbery. The director Michael Blakemore in his acting days was given very short shrift when he auditioned for the Royal Court and said he’d heard Joan Littlewood was even worse, particularly if she suspected you were not working class. ‘One wondered if their avowed intent to change the country was simply a means of replacing one elite with another,’ he said.11

Maybe. But healthy rivalry is no bad thing, and it’s one of the great things about our theatre that it can and does accommodate everyone and everything.

Coming next: Hampstead Theatre Club and the beginnings of fringe theatre

Sources

Clive Barker: ‘Closing Joan’s Book, some personal reminiscences’, from New Theatre Quarterly 74: Volume 19, Part 2

Michael Blakemore, Arguments with England

Joan Littlewood, Joan’s Book: The Autobiography of Joan Littlewood

Howard Goorney and Ewan MacColl, eds, Agit-prop to Theatre Workshop

Peter Rankin, Joan Littlewood: Dreams and Realities

In the Company of Joan Littlewood, Wendy Richardson, YouTube

Joan Littlewood: Dreams and Realities, Peter Rankin

Agit-prop = agitation propaganda, which originated in Soviet Russia and was defined as left-wing political theatre made by and for the working class

Introduction to Agit-prop to Theatre Workshop, eds Howard Goorney and Ewan MacColl

Ibid

For reasons I’m not clear about, but partly to reflect his parents’ Scottish heritage

His most famous song was The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face, which he wrote for his to-be third wife Peggy Seeger. His daughter by his second marriage, Kirsty MacColl, became a well-known singer in her own right. He remained friendly with Joan till the end.

The play has been revived many times, not least in a 50th anniversary celebration at Stratford East, which I attended back in 2013. It still packed a bigger punch than almost anything else I’ve ever seen.

Clive Barker: ‘Closing Joan’s Book, some personal reminiscences’, from New Theatre Quarterly 74: Volume 19, Part 2

Ibid

In the Company of Joan Littlewood, Wendy Richardson,

Arguments with England, Michael Blakemore