(Apologies for the break in transmission due to illness)

As April 2025 draws to a close along with this book, how is the world of theatre looking here in London?

According to SOLT (The Society of London Theatre) ‘Five years after the pandemic, audiences have returned in record numbers, cementing the West End’s status as the world’s premier theatre destination.’1 They record an 11% increase in theatre attendance since before the pandemic, outperforming Premier League football and welcoming ‘nearly 5 million more audience members than Broadway’.

Really?

A quick glance at bookings for West End shows confirms it’s looking pretty buoyant; even long-running musicals such as Les Mis and Tina Turner are still booking healthily, top price over £200 and mid price anywhere from £80 upwards. Recent productions of The Seagull starring Cate Blanchett were apparently charging £450 a ticket and Much Ado at Drury Lane with Tom Hiddleston and Hayley Atwell upwards of £250. (Whether or not the stars of these shows approve these outrageous prices I have yet to find out.)

In the subsidised sector on the other hand the production of new material is down by 30 percent due to a dive in funding. If both these statistics are true it effectively means the icing on the theatre cake is looking enticing while underneath the foundations are crumbling; as there’s no question unless a total diet of musicals is your thing without a healthy injection of experimental input from the fringe the future of creative theatre is at risk.

On the upside there have recently been some serious, and innovative, productions on view in the West End and at the unsubsidised Old Vic: no fewer than two productions of Oedipus and one of Elektra, two of which featured Hollywood stars. The West End Oedipus was directed by Robert Icke and featured our own Mark Strong and Lesley Manville, the Old Vic’s starred Hollywood’s Rami Malek and our Indira Varma and was co-directed by the afore-acclaimed Matthew Warchus and choreographer Hofesh Schechter. I saw neither production, not for want of trying rather than want of availability of tickets and cash. (Ticket prices for the Old Vic were way over £100.2)

Elektra, directed by Daniel Fish, whose radical Oklahoma recently packed out Wyndham’s Theatre, moved the goalposts from Ancient Greece to modern punk, complete with weird recitative and mikes, and largely got the thumbs-down from the critics (except for The Guardian), despite the also-appearance of the hugely talented Stockard Channing. The West End Oedipus got the thumbs-up, the Old Vic version not. Nobody seemed to think much of Rami Malek while praising his co-star Indira Varma. Which might indicate we have a subliminal prejudice against Hollywood stars appearing on our stages, or that they are simply not used to performing in theatre.3 Despite that it is heartening to know there is innovation in the commercial sector, and like all experiments they don’t necessarily succeed.

The public sector

It’s not looking so good in the public sector however. According to a survey conducted by Warwick University ‘Local government revenue funding of culture and related services decreased by 29% in Scotland, 40% in Wales and 48% in England, alongside rising cost and demand pressures on statutory services (especially social care)’; Arts Council funding has decreased by 30 percent and, inexplicably, ‘Tax relief for the creative industries increased by 649%’.4 All of which has led to the closure of many public libraries and in the case of some subsidised theatres a complete axing of public funding and a reduction in grant funding of the BBC. All of it bad news.

To add to the gloom it seems arts education in schools is disappearing fast. Schools can no longer afford to take their charges to theatres and lack of funding means the arts, not considered by successive governments as ‘strategically important’, are the first to be sacrificed. According to the same source the number of arts teachers in state secondary schools has fallen by 27%, the number of students studying the arts has dropped and most importantly, the overall level of engagement in the arts in schools has decreased by roughly a third.

This is seriously bad news, as anybody knows interest in the arts at a young age is crucial. Kids growing up knowing nothing about music or theatre are far less inclined to take part in it in adult life, either as a performer or an audience member.

Most crucially, and speaking from direct experience, drama is an extremely useful teaching tool. I worked for some years with primary school-aged children in schools and with a company I co-formed with a musician and choreographer. Not only were we able to bring a number of topics from the curriculum to life through drama, the children who otherwise were neither particularly academic nor sporty often came to life when asked to perform. As I’ve said more than once before actors are by and large a shy bunch, more confident in the skins of others than in their own. The same applies even more so to young people.

Actors

Many years ago, in my poly-career life, I acted as a playscout for a theatre agent based in Germany. My remit was to look for new plays for possible production overseas, which meant I covered the fringe pretty comprehensively. A number of plays were deemed unsuitable because of their ‘Englishness’, but more than a few of them were turned down because, as my employer told me, they were fringe plays and Germany did not have the depth of acting talent that we have in the UK, which meant they’d be impossible to cast.

I was surprised to hear that because Germany has always been in our eyes a shining example of a country that supports and celebrates the arts far more generously than the UK. Actors there, I understood, enjoyed the security of long contracts and guaranteed employment – which, according to my employer, made them complacent. Only newcomers and students were prepared to work in what they had of a fringe, which wasn’t much.

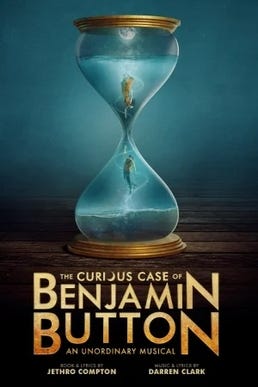

I’m talking of a long time ago and things may have changed there since. But what is unarguable is the astonishing talent you can see in the fringiest of fringe theatres right now. It’s very rare to see a duff performance. As witnessed recently with Southwark Playhouse’s The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, a bunch of unknown young actors act, sing and instrumentalise their way through an entire show so effectively the show has transferred to the West End and won a bunch of awards.

All is definitely not lost.

Is there such a thing as a theatre actor?

What with television, film and streaming there are not many actors these days who stick – or can afford to stick – exclusively to theatre. Many if not most claim it’s their preferred medium, and it’s certainly the most exposing. There is no director or editor to cut out your duff bits, and there is an audience who will tell you plainly what it thinks of you right then and there.

But a number if not most of our major actors still appear regularly on stage. Notable among them are Simon Russell Beale, who does stick mainly to theatre, Kenneth Branagh – one of the few actor-managers of these days – Ian McKellen, appearing recently on stage in his eighties, Harriet Walter, Helen Mirren, Imelda Staunton, David Tennant, Michael Sheen, Ben Whishaw, Lesley Manville, Andrew Scott, Ralph Fiennes, Indira Varma, Paapa Essiedu, Benedict Cumberbatch, Martin Shaw, Ewan McGregor and Gary Oldman, who has returned to the town of his debut, York, with his own production of Beckett’s Krapp’s Last Tape. All these actors are big enough to draw audiences. And we still welcome stars from across the pond such as John Lithgow in the Royal Court’s transfer of Giant and Bryan Cranston, soon to be seen in Arthur Miller’s All My Sons.

Women in theatre

Playwrights, including Caryl Churchill, April de Angelis, Timberlake Wertenbaker, Lucy Prebble, Rebecca Lenkiewicz, , Winsome Pinnock, Lucy Wade, Polly Stenham, Debbie Tucker Green, Lucky Kirkwood, Nina Raine, to name a few; directors Marianne (War Horse, Curious Incident) Elliott, Lyndsay Turner, Rebecca (Cabaret) Frecknall, Phyllida Lloyd, Carrie Cracknell, ditto; producers Sonia Friedman and Nica Burns; artistic directors Josie Rourke, Jude Kelly and Vicky Featherstone; the RSC is currently headed by co-Artistic Directors Erica Whyman and Daniel Evans and for the first time ever the National Theatre has appointed a female artistic director in Indhu Rubasingham, late of the Kiln Theatre (that she ridiculously renamed from the Tricycle) – who has just announced an extremely ambitious programme of new and old plays front-lining female directors and playwrights.

These are the just the tips of the icebergs who are responsible for our theatre. I’m sure there are other shining lights – in the regions particularly – and apologies for not including them. We’ve come a long way from women being banned from our stages.

Reasons to be cheerful

We know theatre will survive, and thrive, and continue to innovate despite the odds, not least because of the determination and the talent of the people who work in it. British governments in modern times have proudly claimed our country as the theatre capital of the world while rarely going near a theatre themselves and gradually reducing financial support. In tough times it’s hard to claim theatre deserves money more than the health service or education, though it’s also possible to argue art that throws light on who we are and the world we have made for ourselves, and throws a bit of joy into our lives, is not just good for general health and well-being but essential for growing generations to understand what life is about.

There are many reasons to be cheerful. In the past ten years three major new theatres have cropped up in London: the Bridge near Tower Bridge, the creation of ex-National Theatre Nicks Hytner and Starr, Nica Burns’ @sohoplace right in the heart of London – which incidentally was built during lockdown and opened soon afterwards – the Troubadour at Wembley Park (and another opening in Canary Wharf later this year). I’ve also just heard permission has been granted to reconvert the Odeon Cinema in Shaftesbury Avenue back into the Savile Theatre. The West End is still innovating here and there, and filling its theatres – albeit with the better-off. Future generations have much to look forward to, if they can afford it.

London’s West End: A Cultural and Economic Powerhouse. https://solt.co.uk/londons-west-end-a-cultural-and-economic-powerhouse/

Which doesn’t compare with, for instance, over $900 for a ticket to see Othello on Broadway with Denzel Washington and Jake Gyllenhaal.

I did hear neither actor had what we might call a ‘theatre voice’, relying heavily on mics.

The State of the Arts, University of Warwick. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.campaignforthearts.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/The-State-of-the-Arts.pdf Tax relief for films appears to be twice as much as for theatre for some reason. (https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-10093/)